On December 18, 1782 in Celtic History

Prisoners in armagh and long kesh end their 53 day hunger strike on promises of political status. the promises are not kept

A hunger strike in 1980 was also undertaken by seven men in the H-Blocks and three women in Armagh Gaol, but it ended on 18 December after 53 days, without any gains for the prisoners.

On 27 October 1980, republican prisoners in in Armagh and Long Kesh (also known as the Maze Prison) began a hunger strike. One hundred and forty-eight prisoners volunteered to be part of the strike, but a total of seven were selected to match the number of men who signed the Easter 1916 Proclamation of the Republic.

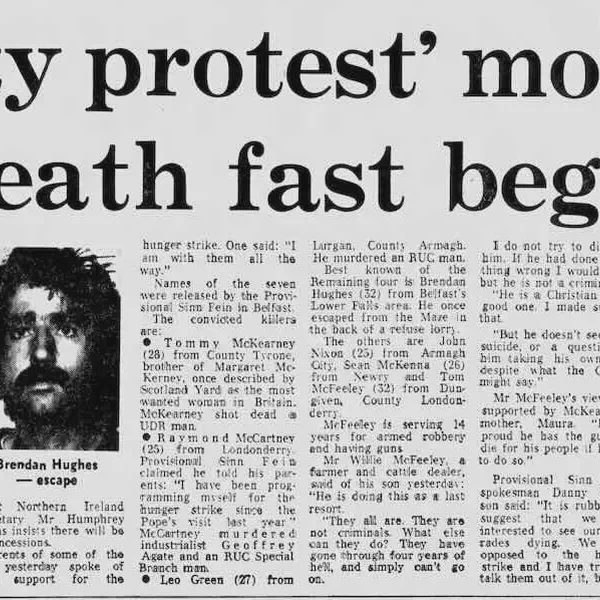

The group consisted of IRA members Brendan Hughes, Tommy McKearney, Raymond McCartney, Tom McFeely, Sean McKenna, Leo Green, and INLA member John Nixon.

Dirty Protest

On 1 December three prisoners in Armagh Women’s Prison joined the strike, including Mairéad Farrell, followed by a short-lived hunger strike by several dozen more prisoners in HM Prison Maze.

Ended 53 days later

In a war of nerves between the IRA leadership and the British government, with Sean McKenna lapsing in and out of a coma and on the brink of death, the government appeared to concede the essence of the prisoners’ five demands with a thirty-page document detailing a proposed settlement. With the document in transit to Belfast, Brendan Hughes took the decision to save Sean McKenna’s life and end the strike after 53 days on 18 December.

Promises are not kept

In January 1981 it became clear that the prisoners’ demands had not been conceded. On 4 February the prisoners issued a statement saying that the British government had failed to resolve the crisis and declared their intention of “hunger striking once more”. The second hunger strike began on 1 March, when Bobby Sands, the IRA’s former Officer Commanding (OC) in the prison, refused food. Unlike the first strike, the prisoners joined one at a time and at staggered intervals, which they believed would arouse maximum public support and exert maximum pressure on Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher.

History

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, inmates affiliated with Irish Republican groups, such as the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and the Irish National Liberation Army (INLA), engaged in a series of hunger strikes. These prisoners were demanding to be treated as prisoners of war or political prisoners rather than as common criminals, a status that had been revoked in 1976 by the British government. This revocation led to protests by prisoners, including the “blanket” and “dirty” protests, culminating in the hunger strikes.

The hunger strikes in Armagh and Long Kesh were particularly notable. The strikers demanded concessions from the British government that included the right not to wear prison uniforms, the right not to do prison work, the right to associate with other prisoners, and the right to organize educational and recreational pursuits.

In some instances, the British government appeared to make concessions to end the hunger strikes. For example, in 1980, a hunger strike at Long Kesh ended after 53 days when the prisoners believed they had been offered a deal by the British government that would meet many of their demands. However, the prisoners later felt that the British government had not fully honored these promises, leading to a sense of betrayal and exacerbating tensions.

Bobby Sands

The most famous hunger strike began in 1981 and was led by Bobby Sands, an IRA member. Sands and other strikers sought to regain political status through their actions. The 1981 strike had a significant impact both within Northern Ireland and internationally, drawing attention to the prisoners’ cause and the broader issues surrounding the Troubles.

The hunger strikes were a turning point in the Troubles, highlighting the depth of the political and sectarian divisions in Northern Ireland. They also had a substantial impact on the political landscape, including the electoral success of Sinn Féin, the political wing of the IRA. The strikes brought international attention to the conflict in Northern Ireland and were a catalyst for subsequent political developments.

The legacy of the hunger strikes is complex, reflecting the broader complexities of the Troubles. They are remembered as a symbol of resistance and sacrifice by Irish nationalists and republicans, while others view them as part of a tragic period in Northern Ireland’s history marked by intense violence and suffering. The issue of political status for prisoners remained a contentious topic long after the strikes ended.

More From This Day

Joseph James O'Neill, writer and civil servant, was born 18 December 1878 at Tuam, Co. Galway

December 18, 1878